*Featured image: Samples of brain tissue, frozen at -150 degrees celsius.

On 23rd August, co-founder Ali Turnbull visited BRACE and the South West Dementia Brain Bank. Here she describes her visit.

Meeting BRACE

While we always try to make sure that each round of Remembering Not to Forget grants are used to fund a wide range of work supporting people impacted by dementia, funding research has always been a key priority for us. We’re really pleased to have been able to donate to BRACE, a small charity supporting dementia research across South West England and South Wales, in all three rounds of funding so far. For each grant we give out there are many emails/ phone calls to discuss how the money will be used to ensure maximum impact, so it was great to have the opportunity to put a face to a name and meet the CEO of BRACE, Mark Poarch, after 3 years of remote communications!

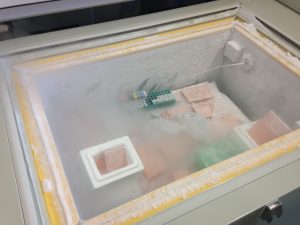

In the last round of funding we gave £3,500 towards the cost of buying a freezer (total cost £10,000) to support the work of the South West Dementia Brain Bank, through BRACE. The Brain Bank contains brain tissue donations from over 1,000 people with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, as well as from older people without any memory problems. The tissue is frozen and fixed so it can be stored long-term, and can then be used over decades, supporting research in South West England, the rest of the UK and internationally. BRACE helped to establish the Brain Bank in the early 1980s, and both BRACE and the Brain Bank are based at Southmead hospital in Bristol.

Funding makes a difference

I was shown round the Brain Bank by Candida Tasman, Brain Bank Technician, who explained the process of receiving donated brain tissue and the huge impact such donations have. When the brain tissue arrives at the Brain Bank it is split into two – one half of the brain is frozen for use in future research (at -80 and -150 degrees C), and the other half is stored in formalin and used to obtain the diagnosis needed before the tissue can be made available for research. While freezers aren’t something I normally get excited about, these freezers were an exception; it was so great to be able to see where our money had gone. BRACE tell us that donors are often not that interested in funding lab equipment, but it’s perfect for us – with our relatively small-scale funding we can’t fund entire research projects, but with this grant we were able to make a tangible difference to ongoing dementia research.

Ali with Candida Tasman, Brain Bank Technician, in front of the freezers, one of which Remembering Not to Forget helped to fund.

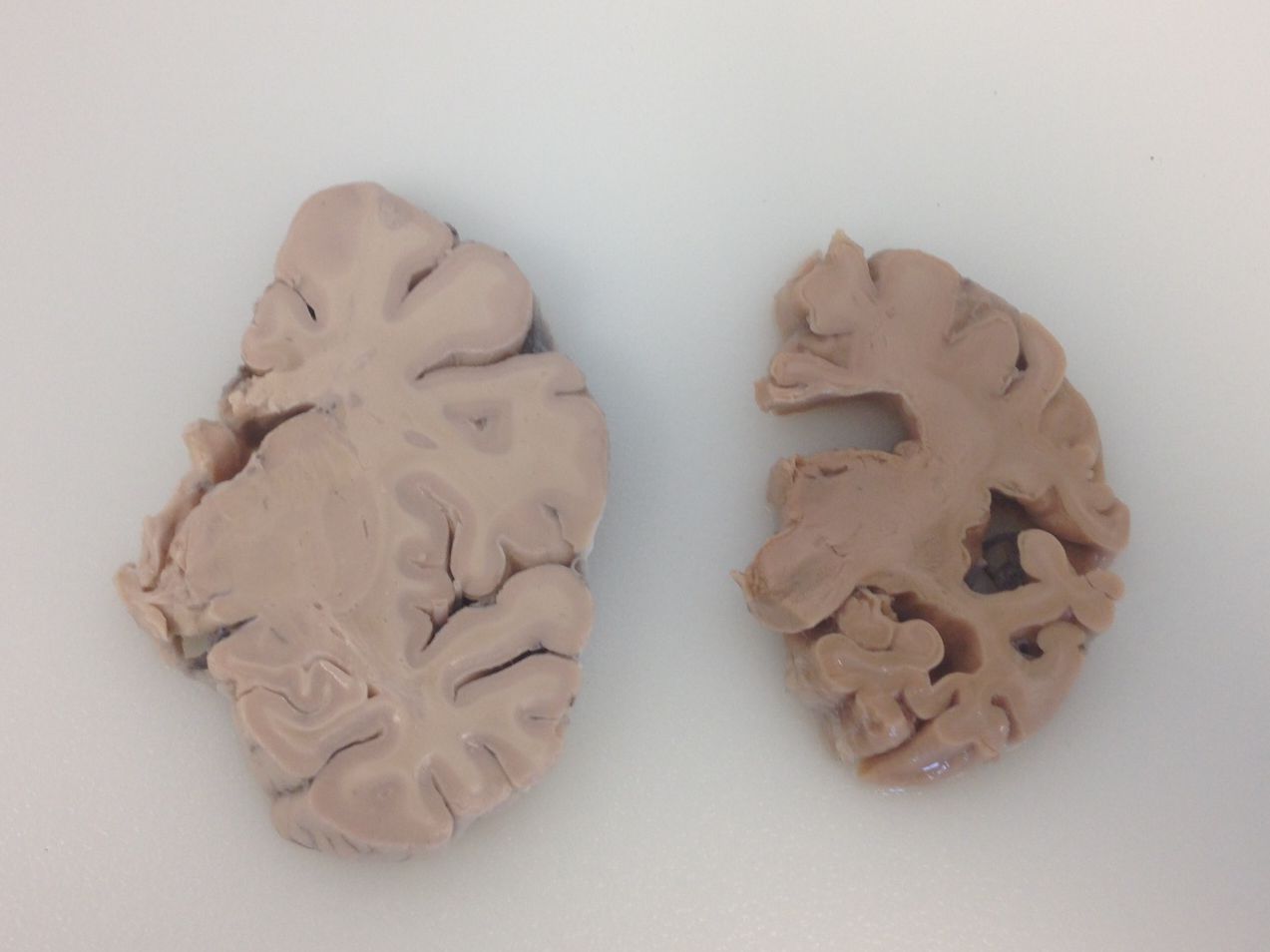

Next, we visited the lab where I saw the formalin-fixed half of the brains and had the process of dissection explained to me. Seeing half a brain out on a table was a bizarre experience – to know that the lump of tissue in front of me had once contained everything about someone that made them who they were. Squeamishness aside, what made the most impression on me were contrasting brain samples Candida showed me – one cross section of healthy brain tissue and one of the brain of someone with Alzheimer’s disease (see below). It was shocking to see the physical impact the disease wreaks, the visible atrophy caused by the proteins which build up in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients to form ‘plaques’ and ‘tangles’. These structures lead to the loss of connections between nerve cells, and eventually to the death of the nerve cells and loss of brain tissue.

A sample of healthy brain tissue (left), and one ravaged by Alzheimer’s disease (right).

In addition to contributing to research into possible treatments for different types of dementia and increasing our understanding of how these diseases develop, the Brain Bank also provides an accurate diagnosis of the type of dementia the donor was living with. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, accounting for about 62% of cases, but there are many different types of dementia, and even within the four most common types of dementia (Alzheimer’s, Vascular Dementia, Dementia with Lewy bodies, Frontotemporal Dementia) there are different subsets. Dementia affects everyone differently, but there are definite patterns both of the progression of different forms of dementia, and the impact on the person living with the dementia. However, studies suggest that of the people who have a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, up to 40% are found to have a different type of dementia or mixed dementia at post-mortem examination*. An improved diagnostic process will therefore provide:

- a clearer idea of what to expect, how to recognise and respond to the vagaries of the specific form of this cruellest of conditions

- an increased likelihood of accessing appropriate forms of treatment

- an opportunity to plan appropriately for the future

- overall (and most importantly), more chance of living well with dementia for longer.

Brain tissue donation

When I first drafted this write up of my visit, I’d planned to include details of how potential donors could sign up to support the incredible work happening at the Brain Bank. I was mulling over the wording as I was aware it was a sensitive issue.

All that changed on 1st September when my lovely mum died. I’d taken away the forms about brain tissue donation from my visit to the Brain Bank, and my sister and I had agreed that, as a vocal advocate for organ donation and scientific research, Mum would have wanted to donate her brain tissue. Although she’d been fading all summer, we weren’t prepared to lose her so suddenly and we hadn’t yet had a chance to discuss it with my Dad, or with Mum (we discussed all care decisions affecting Mum with her, even though she showed little signs of comprehension and her words had all but disappeared by the end). We knew there was a limited window to arrange the donation for the tissue to remain viable, so in the blur of those first few hours after her death we discussed it as a family and agreed to contact the Brain Bank to start the process.

The staff at the Brain Bank couldn’t have been lovelier or more understanding as I struggled to hold it together over the phone while we completed all the paperwork. They, amazingly, managed to put all the logistics in place to arrange the donation that afternoon. Although thinking about the reality of the tissue collection taking place was difficult (cutting my mother’s brain out? Are we really doing this??) I haven’t for one second regretted it. My Mum spent her whole life helping people, and through the research at the Brain Bank she will continue to help hundreds, if not thousands, of people after her death. It feels like a fitting legacy, and is something that has been a real comfort through the ups and downs of the past few weeks.

If you’d like to find out more about the process of donating brain tissue, please visit the Brain Bank website.

*Statistic provided by the Brain Bank.

One reply on “Visiting the Brain Bank”

Simon (the old Popsicle) November 11, 2017 at 7:27 pm

Beautifully written, my dear!

Comments are closed.